Important: You can find the most recent information on both the OpenITI and the OpenITI mARkdown at the website of the KITAB project: http://kitab-project.org/corpus-and-data. Information below is of value mainly as a record on the history of the OpenITI initiative.

- Description of the OpenITI: https://maximromanov.github.io/OpenITI/

- Description of the OpenITI mARkdown (the earliest stable version): https://maximromanov.github.io/mARkdown/

Open Islamicate Texts Initiative (OpenITI) is a multi-institutional effort to construct the first machine-actionable scholarly corpus of premodern Islamicate texts. Led by researchers at the Aga Khan University (AKU), University of Vienna/Leipzig University (LU), and the Roshan Institute for Persian Studies at the University of Maryland (College Park) and an interdisciplinary advisory board of leading digital humanists and Islamic, Persian, and Arabic studies scholars, OpenITI aims to provide the essential textual infrastructure in Persian and Arabic for new forms of macro textual analysis and digital scholarship. In the process, OpenITI will enable new synergies between Digital Humanities and the inter-related Islamicate fields of Islamic, Persian, and Arabic Studies.

Currently, OpenITI contains almost exclusively Arabic texts, which were put together into a corpus within the OpenArabic project, which was developed first at Tufts University (at The Perseus Project, 2013–2015) and then at Leipzig University (at the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for Digital Humanities, 2015–2017), in both cased with the support and under the patronage of Prof. Gregory Crane.

General Description

The goal of OpenArabic is to build a machine-actionable corpus of premodern texts in Arabic to encourage computational analysis of the Arabic literary tradition. Most of the texts have been collected from open-access online collections of premodern and modern Arabic texts such as http://shamela.ws/ and http://shiaonlinelibrary.com/ (These texts have Shamela+NUMBER and Shia+NUMBER; some texts are coming from al-Jāmiʿ al-kabīr, which has been published on an external HDD and is not available online (JK+NUMBER). Initial metadata from these collections is preserved at the beginning of each file.

Currently uploaded texts have been automatically converted into the OpenITI mARkdown format—a flavor of markdown that was developed for tagging premodern Arabic text. All of our texts require further editing to properly tag their structures. A detailed description of the mARkdown scheme and the tagging workflow can be found in the OpenITI mARkdown section. When manual tagging is complete the texts will be converted into a CTS-compliant XML format.

For the list of books currently included in the corpus, see below.

The overall organization of OpenITI

The corpus is available on GitHub (https://github.com/OpenITI). Books are grouped into authors. All authors are grouped into 25 AH periods, based on the year of their death. These repositories are the main working loci—if any modifications are to be added or made to texts or metadata, all has to be done in files in these folders.

There are three types of text repositories:

RAWrabicaXXXXXXrepositories include raw texts as they were collected from various open-access online repositories and libraries. These texts are in their initial (raw) format and require reformatting and further integration into OpenITI. The overall current number of text files is over 40,000; slightly over 7,000 have been integrated into OpenITI.XXXXAHare the main working folders that include integrated texts (all coming from collections included intoRAWrabicaXXXXXXrepositories).i.xxxxxrepositories are instantiations of the OpenITI corpus adapted for specific forms of analysis. At the moment, these include the following instantiations (in progress):i.cexwith all texts split mechanically into 300 word units, converted intocexformat.i.mechwith all texts split mechanically into 300 word units.i.logicwith all texts split into logical units (chapters, sections, etc.); only tagged texts are included here (~130 texts at the moment).i.passim_new_mechwith all texts split mechanically into 300 word units, converted for the use with newpassim(JSON).- [not created yet]

i.passim_new_mech_clusterwith all text split mechanically into 900 word units (3 milestones) with 300 word overlap; converted for the use with newpassim(JSON). i.passim_old_mechwith all texts split mechanically into 300 word units, converted for the use with oldpassim(XML, gzipped).i.styloincludes all texts from OpenITI (duplicates excluded) that are renamed and slightly reformatted (Arabic orthography is simplified) for the use withstyloR-package.

Repositories and Folder Structure

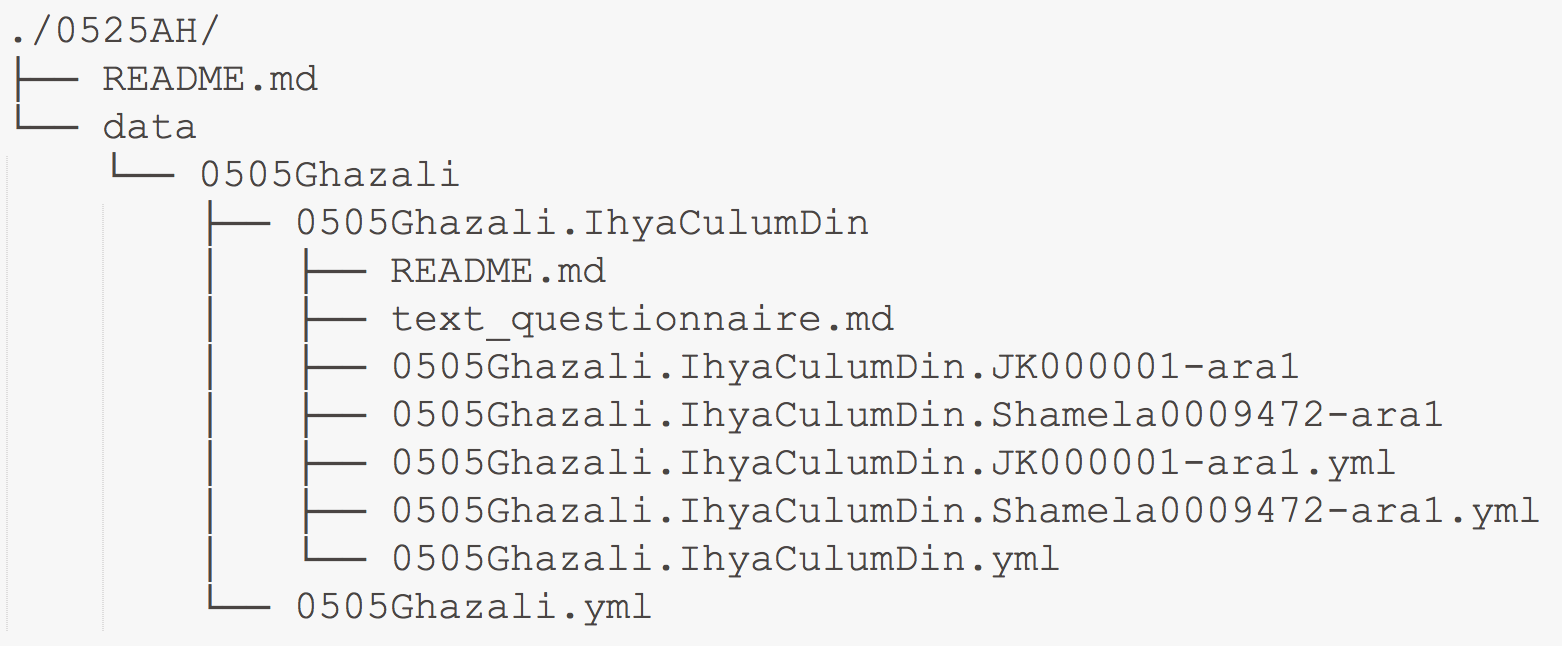

OpenITI corpus is organized in compliance with CTS guidelines as they are implemented in the CapiTainS Suite, developed by Bridget Almas and Thibault Clérice at Tufts University and Leipzig University (http://capitains.org/), although the conversion into TEI XML is yet to be implemented. The entire corpus is divided into a series of repositories. Each repository covers a chronological period of 25AH lunar years: 1) the main folder within each repository is data, which contains subfolders for each author who died within a given period; 2) each author’s subfolder includes subfolders for this author’s books (often in multiple versions). For example, the repository 0525AH includes authors whose death dates fall in the range of 501–525 AH). Below is an example of how al-Ġazālī’s Iḥyāʾ ʿulūm al-dīn fits into the corpus.

From this example, you can see that the repository 0525AH includes a subfolder data, which includes a subfolder with al-Ġazālī’s URI, 0505Ghazali, which then includes a subfolder with Iḥyāʾ ʿulūm al-dīn URI (uniform resource identifier), 0505Ghazali.IhyaCulumDin, which then includes all the relevant files. NB: README.md files contain some technical descriptions for a relevant level; *.yml files contain machine-readable metadata (On these metadata files see below).

CTS-compliant naming pattern

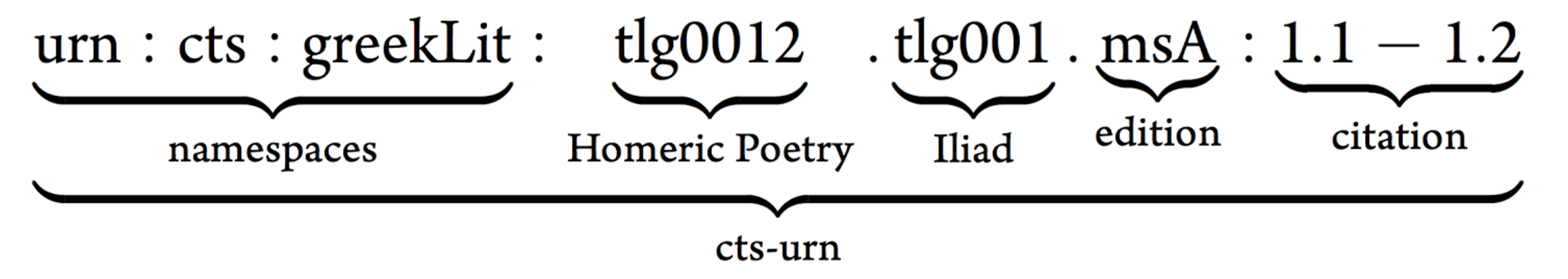

Canonical Text Services, or CTS, offer a powerful mechanism for building expandable and interoperable corpora. The power of the CTS lies in the URN, a uniform resource name (also URI, unique resource identifier), which provide the permanent canonical references to texts or passages of text, and are used by Canonical Text Services (CTS) to identify or retrieve passages of text (For an overview, see CTS Overview). The example of the CTS URN structure is provided above.

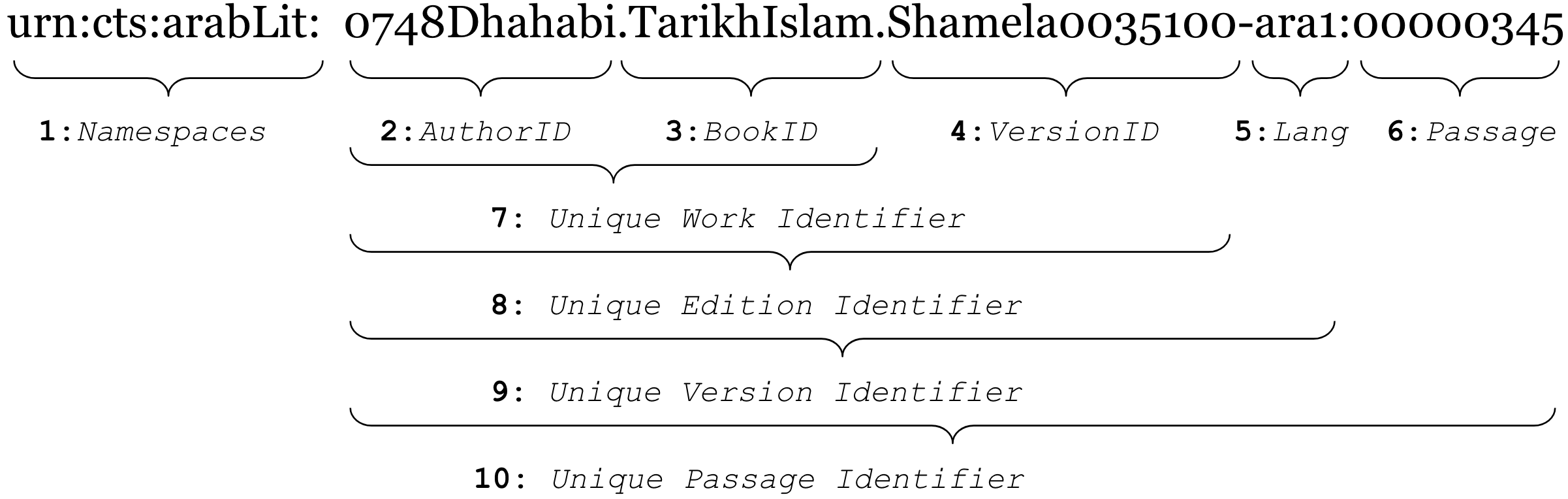

To make this example more understandable in the context of OpenITI, let’s take a look at a practical example of al-Ḏahabī’s Taʾrīḫ al-islām above. In the example above we have the following:

- 1: Namespaces are standard technical parameters from the CTS URN structure which, among other things, allow building and maintaining multilingual corpora.

- 2: AuthorID is the unique identifier for an author, In our case,

0748Dhahabiis the identifier for Šams al-dīn al-Ḏahabī, a famous Damascene muḥaddiṯ and historian, who died in 748/1347. - 3: BookID is an element that identifies a book (book title). Combined with the preceding elements, it becomes 7: Unique Work Identifier.

- 4: VersionID points to the origins of the specific version of a text and allows accommodating multiple versions of the same text; Combined with the preceding elements it becomes 8: Unique Edition Identifier.

- 5: Lang indicates the main language of the text (these are

ISO 639-2codes, see Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages at the LOC website).Langalso allows to accommodate translations of a specific version of a text. For example, the URI0748Dhahabi.TarikhIslam.Shamela0035100-eng1would indicate an English translation of al-Ḏahabī’s Taʾrīḫ al-islām, which is based on the text represented with the URI in the example—0748Dhahabi.TarikhIslam.Shamela0035100-ara1; the number that follows the three-letter language code also allows to accommodate additional versioning. For example, the URI0748Dhahabi.TarikhIslam.Shamela0035100-eng2would represent another translation of0748Dhahabi.TarikhIslam.Shamela0035100-ara1. Combined with the preceding elements, it becomes 9: Unique Version Identifier. - 6: Passage is the ID of a specific text unit (like a chapter, a biography, a paragraph, etc.). Combined with the preceding elements, it becomes 10: Unique Passage Identifier.

A note on the principles of assigning human-readable URIs

Unlike conventional URIs, OpenITI URIs are human-readable and though some would argue that such naming conventions may cause issues, the advantages of having human-readable URIs—at least at this stage of the development of OpenITI—significantly overweight any potential issues. The following principles were followed during the assignment of human-readable URIs (only elements 2, 3, and 4):

-

[2] As a rule, AuthorID is formed by combining (a) the hijrī year of death formatted into a 4-digit number (prepended with

0s, if necessary) and (b) the šuhraŧ of the author, since this is usually the most recognizable element of any author’s name. The year of death in the AuthorID does not have to be exact, if any controversy exists. Even an approximate date will suffice, since it will allow to arrange texts chronologically. Any issues regarding the year death can described in the metadata files (*.yml). -

[3] The BookID is usually formed from one or two recognizable keywords from the title.

-

[4] The VersionID is formed by combining the

nameof a digital library or collection from which the text originates with the unique number of this text in that collection. In cases when texts are provided by individuals or projects, the last name of the provider or the name of the project is used asname, while texts are numbers sequentially within the provided batch.

Additionally, the following rules for coding names and book titles were followed:

- The Library of Congress scheme is followed in its simplified version, omitting all diacritics so that only ASCII characters are used. Two most problematic Arabic letters are dealt with in the following manner: 1) hamzas are omitted to avoid using non-letter characters; 2) ʿayns are transliterated with

c, which is capitalized when appropriate (ʿAlī >Cali; Aʿyān al-šīʿaŧ >AcyanShica). b.part of a name is written in full and capitalized: ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib >CaliIbnAbiTalib.- Although an effort was made to use šuhras for AuthorIDs, in cases when it was not possible, the following formula was followed: Ibn + Ism Abī-hi + Nisbaŧ (these were the onomastic elements most commonly available in the metadata).

- The word kitāb is dropped from the titles, unless it is the major keyword, like in the case of, for example, Sibawayhi’s Kitāb, whose unique identifier is

0180Sibawayh.KitabSibawayh. - Definite articles are dropped everywhere: Tārīḫ al-islām >

TarikhIslam. - Parts of the same entities are written together, in camelcase. In other words, there are no spaces between words, but each word is capitalized:

al-Nāsiḫ wa-l-Mansūḫ>NasikhWaMansukh. - NB: In the beginning, tāʾ marbūṭaŧs were dropped throughout, but later transliterated only in iḍāfas; still fixing that issue…

File extensions

[no extension]: This is a RAW file, automatically converted from its initial format to be as close to the OpenITI mARkdown format as possible. NB: Since the corpus is work in progress and many texts have not yet been manually edited, tags that may appear in texts do not necessarily correspond to proper OpenITI mARkdown tags!*.inProgress: The file has been selected to be fully converted into OpenITI mARkdown and is currentlyin progressof being converted (githublog contains the username of the person who is working on the file).*.completed: The conversion of the file is completed, but the file still requires final verification and vetting.*.mARkdown: The file has been verified and vetted. This version should also have expanded tags and numeric IDs assigned to each logical unit.

In the long run we are envisioning the entire corpus to be converted into TEI XML and becoming available as a library for researchers through some XML-based library framework.

Machine-readable metadata files (*.yml)

Description to be added…

Statistics on the corpus

| Category | Stats |

|---|---|

| Number of text files | 7071 |

| Number of books | 4286 |

| Number of authors | 1857 |

| Length in words (all) | 1,346,418,237 |

| Length in pages (300 w/p) | 4,488,060 |

| Length in words (unique) | 745,390,461 |

| Length in pages (300 w/p) | 2,484,634 |

Lengths of texts

| Words | Pages (300 w/p) | |

|---|---|---|

| Min. | 150 | 0 |

| 1st Qu. | 32,700 | 109 |

| Median | 105,300 | 351 |

| Mean | 306,700 | 1,022 |

| 3rd Qu. | 266,700 | 889 |

| Max. | 10,410,000 | 34,700 |

Chronological Distribution of Texts

| Century CE | Titles | Words | |

|---|---|---|---|

[ |

7th century | 33 titles | 670,7 mln. words |

[][][] |

8th century | 87 titles | 6,1 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][] |

9th century | 509 titles | 31,7 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

10th century | 674 titles | 60,0 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][ |

11th century | 691 titles | 71,2 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

12th century | 464 titles | 53,2 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

13th century | 448 titles | 59,7 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

14th century | 578 titles | 96,8 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][ |

15th century | 328 titles | 72,9 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

16th century | 251 titles | 59,9 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][] |

17th century | 160 titles | 53,5 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][ |

18th century | 151 titles | 33,8 mln. words |

[][][][][][][][][][][][][][][][ |

19th century | 202 titles | 61,2 mln. words |

[][][][][ |

20th century | 129 titles | 16,8 mln. words |

Detailed Lists

- The list of books by centuries

- The list of books by lengths

- Forms, Themes, Genres (provisional assessment)

Preliminary Analysis of Categories of Texts

The following is based on temporary tags derived from The Coverage of the Arabic Collection, in Sections: “Chronological Distribution of Texts” and “Forms, Themes, Genres (provisional assessment)”. Descriptive statistics numbers for “Forms, Themes, Genres (provisional assessment)” are overlapping as most books belong to multiple forms/genres/categories, and often cover multiple themes. At the moment we have almost 4,300 unique Arabic texts in the corpus. This selection of texts covers most thoroughly the period from the 9th till 16th century CE (250–700 titles and 30–90 million words per century), but also offers a decent coverage of 7th–8th and 17th–early 20th centuries. Based on our provisional assessment of this collection using metadata that we were able to gather together with texts, the thematic coverage is quite broad broad and includes all major genres that flourished in the Arabic-Islamic written tradition:

- The broad category of “fine literature”/belles-lettres (adab) includes ca. 600 texts, with over 50 million words; its subcategories—also quite broadly defined—cover such areas as “ethics,” (aḫlāq)—204 titles, with 12 million words; rhetoric (balāġaŧ)—357 texts, with 33,3 million words; poetic theory, or “science of versification” (ʿarūḍ)—9 texts, with 1,9 million words; poetic collections (šiʿr)—196 texts with 8,6 million words (collections of poetry, dīwāns, cover all major historical periods/regions: pre-Islamic, early Islamic, Umayyad, ʿAbbāsid, Andalusi, ʿUṯmānī/Ottoman); collections of sayings and proverbs (amṯāl)—15 texts, with 1,3 million words;

- Geographical texts and travelogues: general geographies (buldān/juġrafīyaŧ)—152 texts, with 32,7 million words; travelogues (riḥlāt)—70 texts, 7,9 million words;

- Historical texts and chronicles (tawāriḫ)—310 texts, 74,4 million words;

- Biographical texts and collections of biographies (siyar, tarājim and ṭabaqāt)—768 texts, with 151 million words;

- Administrative practice (ṣināʿaŧ al-kitābaŧ)—9 texts, 1,9 million words; and governance (siyāsaŧ)—66 texts, with 5,2 million words;

- Genealogical texts (ansāb)—36 texts, with 5,7 million words;

- Islamic religious texts I. The Qurʾān and Qurʾānic sciences, which include: exegesis (tafsīr)—207 texts, 84 million words; qiraʾāt, recitations—29 texts, 2,4 million words; tajwīd, “art of recitation”—16 texts, 1,4 million words;

- Islamic religious texts II.—Tradition and traditionalist sciences (ḥadīṯ); collections of ḥadīṯs—1,970 texts, 226 million words; collections of reliable transmitters (ṯiqāt)—13 texts, 3,3 million words; “analysis of sources” (taḫrīj)—77 texts, 25,3 million words;

- Islamic religious texts IIIa. Islamic law and legal sciences: legal theory (fiqh)—776 texts, with 255 million words; collections of legal decisions (fatāwá)—31 text, with 6,7 million words; IIIb. Teachings of different legal schools: Ḥanafīs—52 texts, 28 million words; Mālikīs—44 texts, 25 million words; Šāfiʿīs—67 texts, 46,3 words; Ḥanbalīs—55 texts, 19 million words; Jaʿfarīs (“Twelvers”)—…; Ẓāhirīs—1 text, 1,5 million words; Zaydīs—3 texts, 1,5 million words;

- Islamic religious texts IV. Theological treatises and dogmatics (ʿaqāʾid): 519 texts, 28,2 million words;

- Doxographical texts: “religious communities” (milal)—230 texts, 12,7 million words; “religious divisions” (firaq)—19 texts, 2 million words; refutations (rudūd)—65 texts, 4,1 million words;

- Medical texts (ṭibb), including both Greek and Islamic traditions—77 texts, with 5,2 million words; (NB: Including a collection of texts prepared by Professor Peter Pormann and his team at U Manchester within the “Arabic Commentaries on the Hippocratic Aphorisms” project—64 texts, with ca. 1 million words);

- Texts by smaller religious communities: Twelver Shiʿites—448 texts, 107 million words; Zaydī Shiʿites—5 texts, ca. 85,000 words); Ṣūfī texts—9 texts, 2,4 million words;

- Greek/Hellenistic tradition—altogether 150 texts, with 2,4 million words, including philosophical (falsafaŧ) and natural sciences texts—93 texts, 4,9 million words (NB: Including texts from “A Digital Corpus for Graeco-Arabic Studies” (http://www.graeco-arabic-studies.org/), whose Arabic section includes 77 texts, with ca. 1 million words);

- Bibliographical texts and collections (fahāris)—54 texts, with 8,2 million words;

- Arabic language: grammar (naḥw)—143 texts, with 19 million words; morphology (ṣarf)—143 texts, 19 million words; lexicons of rare words (ġarīb)—126 texts, with 28 million words;

- Early modern journals (majallaŧ): 8 texts, 9,9 million words;

- Memoires (muḏakkarāt)—11 texts, ca. 1 million words;

- Reference books of different kind: technical terminology of various disciplines (muṣṭalaḥāt)—224 texts, 31,9 million words;

NB: These categories based on the currently available metadata; creating detailed metadata on authors and their books, by the end of the project we will provide a very detailed and precise description of the coverage of this collection.

Leave a comment