Creating Frequency-Based Readers for Classical Arabic

Learning classical Arabic is a long process. (One of my University of Michigan professors once joked that it is hard only for the first ten years—after that it gets worse.) Most of us took great pleasure in advanced reading classes with our professors. Yet, often struggling with the overwhelming volume of new vocabulary, we also—at least occasionally—had a feeling that a traditional method is not necessarily the most effective one. While committed students usually overcome this difficulty by their sheer passion for the subject, the introduction of excessive vocabulary creates a serious obstacle to many truly capable students.

Pervasive availability of electronic texts and computational methods of text analysis allow us to rethink how we teach difficult languages. We can identify the most frequent features within a corpus and focus our attention on them. For example, the 100 most frequent lexical items constitute about 56% of the entire vocabulary of over 34,000 Prophetic sayings (ḥadīṯ) from the Six [Sunnī] Collections (al-kutub al-sittaŧ, approximately 2.8 million words). Relying on such data, one can generate a frequency-based reader that will introduce students to the shortest texts with the most frequent vocabulary and grammatical structures. With a paced increase in difficulty of texts and incremental expansion of vocabulary, students will be able to digest much larger volumes of text both in class and at home, and such an extended exposure will enable students to internalize the authentic language more efficiently. For example, in the course of one semester, we managed to cover about 400 ḥadīṯs, while at the same time reviewing the grammar of classical Arabic and having regular discussions of thematic readings that helped students to understand the cultural importance of the Ḥadīṯ across almost 14 centuries of Islamic history.1

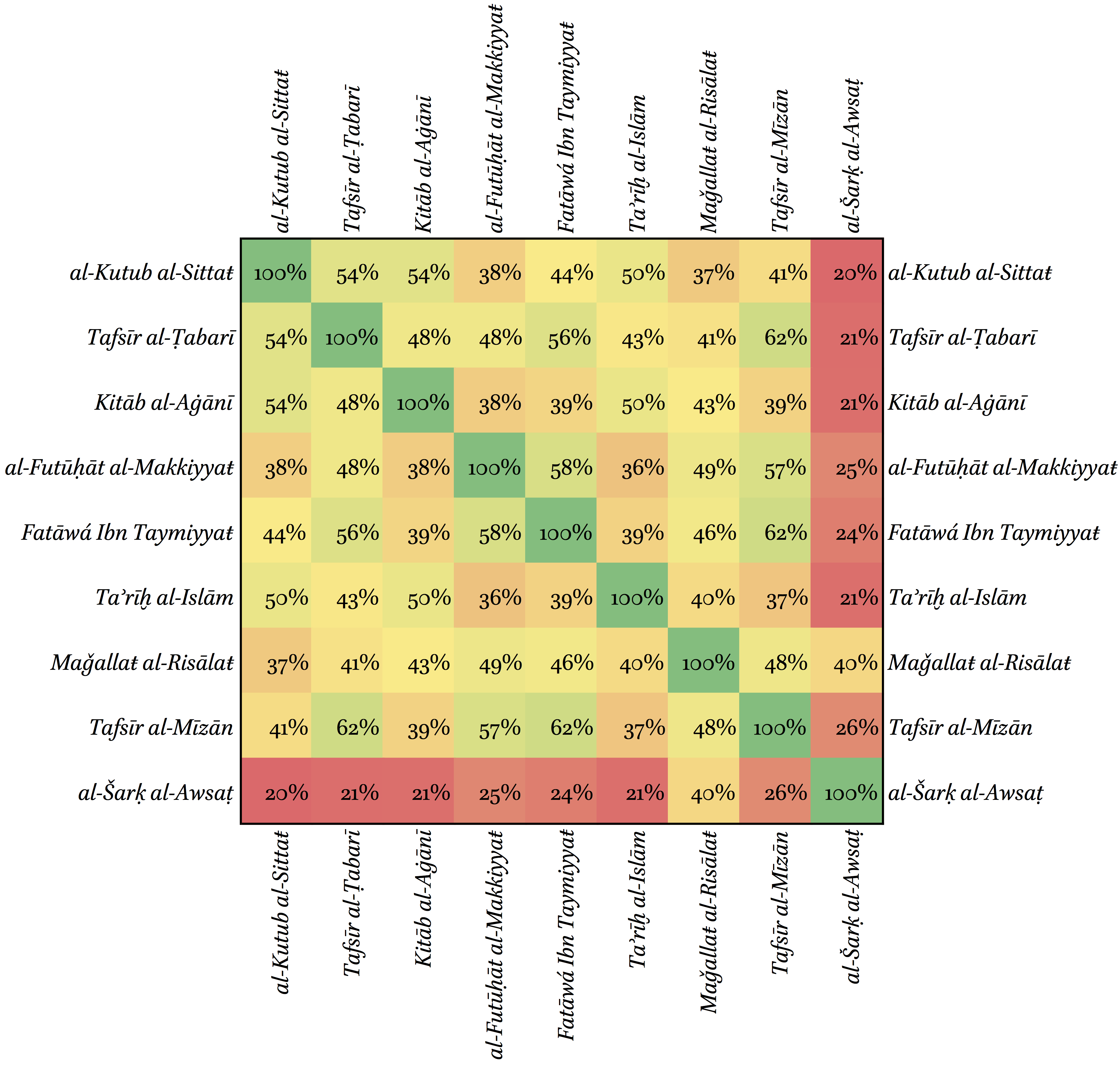

While developed primarily with classical Arabic in mind, the approach is actually universal and can be used for any language. It works best with serialized texts—that is a large corpus of relatively short texts of the same type (in the case of Arabic that would be ḥadīṯ collections, chronicles, biographical dictionaries, poetic anthologies, contemporary newspapers, etc.). Considering that in terms of vocabulary various forms and genres may differ from each other quite significantly (Figure 1 shows that such difference may go up to 80%!), this method can be used to introduce students to the language of particular genres in the most efficient manner. Courses based on such readers can be a valuable addition to any language program and will be particularly welcomed by graduate students who often face the need to develop their readings skills as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Texts compared: al-Kutub al-Sittaŧ (2,8 mln. words), the 6 Sunnī collections of Ḥadīṯ (~9th century CE); Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī (or Ǧāmiʿ al-bayān, 3 mln. words), a commentary to the Qurʾān of al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/922 CE); Kitāb al-Aġānī (1,5 mln. words), a poetic anthology of Abūl-l-Faraǧ al-Iṣbahānī (d. 356/967 CE); al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyyaŧ (1,7 mln. words), an extensive Ṣūfī text of Ibn al-ʿArabī (d. 638/1240 CE); Fatāwá Ibn Taymiyyaŧ (2,9 mln. words), a collection of legal decisions and epistles of Ibn Taymiyyaŧ (d. 728/1327 CE); Taʾrīḫ al-Islām (3,2 mln. words), a biographical collection and chronicle of al-Ḏahabī (d. 748/1347 CE); Maǧallaŧ al-Risālaŧ (16 mln. words), an early 20th-century Egyptian literary journal; Tafsīr al-Mīzān (2,3 mln. words), a modern Šīʿī commentary to the Qurʾān of al-Sayyid al-Ṭabāṭabāʾī (d. 1981 CE); and al-Šarḳ al-Awsaṭ (2,5 mln. words), a modern Arabic newspaper (collected by Tariq Yousef from http://aawsat.com/).

Description of the method

The overall procedure is rather simple and runs as described below.

Step I. Ḥadīṯ collections were downloaded from http://sunnah.com/. Then, initial texts were reformatted and normalized.2 (There are multiple way how specimens of other genres can be obtained and the processed for a similar reader).

Step II. All vocabulary from the corpus was collected and converted into a frequency list. This list was then inverted into a ranking list, where the most frequent item receives rank 1, the second most frequent one—rank 2, the third—3, and so on; items with the same frequency are assigned the same rank. It should be noted that vocabulary items have not been parsed with a morphological analyser, so different forms of the same word are treated separately (i.e., ḳāla, ḳīla, ḳālat, fa-ḳāla, etc. have their own frequencies and ranked separately). The main reason for not using the results of the automatic morphological analysis is largely technical since existing morphological analyzers are meant to work with modern standard Arabic and do not perform well on classical Arabic.3 At the same time, using frequencies of word forms (tokens) rather than dictionary forms (lexemes) has its advantages, since more frequent forms will be given more frequently in the reading materials (such as, for example, very frequent ḳāla [sing. masc.] vs. rather rare ḳālā [dual masc.]).4

Step III. The average mean of ranking values was then calculated for each ḥadīṯ. The resultant values then served as difficulty indices, where texts with the most frequent vocabulary would have the lowest average means, and vice versa. These indices were then used as sorting values that allowed rearranging all 34,000 ḥadīṯs by the difficulty of their vocabulary. The advantage of the average mean here is that even a single low-frequency lexical item increases the difficulty index of a text, which is pushed down the list. This approach turned up a couple of unforeseen positive effects. First, as the length of a text increases so does the probability of rarer lexical items—as a result, the “easiest” texts are also the shortest ones. This convenient outcome allows students to begin with the shortest texts and move gradually to the longer ones. The second effect is that the most frequent vocabulary also tend to appear in the most frequent grammatical and syntactic structures.

Step IV. The rearranged collections of ranked ḥadīṯs were not quite useable since this method also groups together items that are almost the same. Here manual revision was required to exclude ḥadīṯs that are too similar.

Step V. At last, the selection of ḥadīṯs was converted into LaTeX format and typeset into the reader in front of you. As you will see, quite a few ḥadīṯs in the beginning of the reader feature only isnāds, “the chains of transmitters”, and do not have matns, the actual texts of ḥadīṯs. I used these matn-less ḥadīṯs to introduce students to the concept of transmission of knowledge in Islamic culture, which most were not familiar with; next time around I will modify the reader to avoid having very similar texts next to each other, which can be done by the retagging of the selection of ḥadīṯs and regenerating the entire reader anew.

In the classroom

In my teaching, I used this reader in combination with ‘micropublications’, which provided each student with a thorough practice of foundational skills necessary for mastering the language: for each ḥadīṯ students provided full vocalization, morphological stemming, and translation aligned with its Arabic original. Such ‘micropublications’ help monitoring students’ progress, and, later, can be used to automatically grade such assignments, thus freeing up time for in-class discussions. Last but not least, by producing these micropublications, students make a valuable contribution as they generate training data that can be used for various teaching and research purposes.

Footnotes

“Classical Arabic through the Words of the Prophet” (Tufts University, Winter/Spring 2015), with the following two additional readings: W. M. Thackston, An Introduction to Koranic and Classical Arabic: An Elementary Grammar of the Language (Bethesda, Md.: Ibex Publishers, 2000), Jonathan Brown, Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World (Oxford: Oneworld, 2009).↩

On normalization, see: Nizar Y. Habash, Introduction to Arabic Natural Language Processing ([San Rafael, Calif.]: Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2010), 21–23.↩

For example, Buckwalter Morphological Analyser, which has been tested with this corpus (using Perseus morphological services), returned no results for about 25% of tokens, single results for another 25%, and more than one for the rest 50%. Needless to say, such results are hardly useable for our purposes.↩

An ability to recognize rare forms is important, of course, but it can be practiced through grammatical and morphological exercises (examples can be found at the end of the reader).↩